Not for the Flesh: A 600-Year-Old Vegan Catholic Tradition of Animal Liberation

2025-05-19Being raised as an ethical vegetarian in the West meant being in the minority. It rarely caused tension, but when it did, people would sometimes push on my dietary choices by turning to the scriptures. “But God put animals on Earth for us!” I was told more than once over the years.

And so I grew up taking it for granted that my family’s choices were not just exotic, but alien to the dominant faith in North America and Europe. Seventh Day Adventists excepted, my ethical brethren when it came to vegetarianism belonged to the Eastern religions like Hinduism and Buddhism. Years passed. I became vegan in 2003, at which point I did not ever consider my ethical choices to be in communion with any major Christian denomination, and certainly not Catholicism.

All this made the discovery of the small but extant Catholic Ordo Minimorum–the Order of Minims–both unexpected and worthy of sharing.

Founded in 1435 by the hermit Saint Francis of Paola (who was named after and inspired by the earlier and more famous Saint Francis of Assisi), the Minims are distinguished from other Mendicant orders by having a fourth vow, a voto di perpetua quaresima, a vow of perpetual Lent, in addition to the customary three of poverty, chastity, and obedience.

To Francis, the fourth vow required a complete and lifelong abstention from consumption of meat, and anything derived from it, such as eggs, butter, cheese, milk, leather, and other similar items. These were also banned from the order’s homes and cloisters1.

A Catholic order that’s been following a strict plant-based diet and lifestyle for nearly 600 years is already surprising enough, but the alignment between the spiritual justification for what I call the Paolan vow—the commitment to perpetual abstinence from all animal products—and modern anti-speciesism and animal liberation is revelatory.

According to the 16th-century theologian and Minim Friar Francesco di Longobardi, St. Francis of Paola saw the eating of flesh as the consequence of corruption after Eden, when humanity “degenerated”. Jesus, Francis believed, restored the original abstention from eating meat, not as a commandment, but as advice to those who aspired for greater perfection. The primitive church, the Church of Jesus’ apostles, had understood and had followed Jesus’ advice, the Hermit argued. And the Minim’s Paolan vow sought to emulate this earlier, more perfect church.2

See footnotes for Italian text and English translation.

In daily practice, the Minims’ vow of perpetual lent and my ethical veganism are virtually identical. But there’s a compelling and profound kinship between St. Francis of Paola’s teachings and my contemporary ethics that go beyond how we nourish ourselves.

While ethical vegans believe in the idea of anti-speciesism and the liberation of animals, I argue Francis reached similar conclusions theologically by invoking a pre-Fall Edenic life that was corrupted and then restored, as appropriate for his time and context. For Francis, animals were not objects, to be used and disposed of for their flesh, but full members of creation–the animal Brothers and Sisters of the earlier St. Francis of Assisi, now reaffirmed by the Hermit from Paola.

The Hermit’s interpretation of Eden is of a world where no flesh is consumed by humans and where butchers, slaughterhouses, and grazing allotments have no reason to exist, a world where CAFOs and ventilation shutdowns3 are never even conceived. It is an Eden where animals never knew repression and lived in liberation. He sought personal perfection through his abstinence from meat and animal products, but he also pushed for collective action by founding a Catholic order and instituting a fourth vow of spiritual veganism, sidestepping the issue of calling for a general prohibition on eating meat by showing his contemporaries why the life of animals mattered.

This is as close to a pre-modern vegan and animal liberation ethic in the West as I’ve ever found. While it isn’t enough to make me a full-on believer, it is certainly enough to make the Catholic Minims my ethical Brothers and Sisters when it comes to our orientation towards non-human animals, and that’s meaningful for someone who, for decades, saw little common ground with the Pope’s church on this issue.

Today, the Order of the Minims is a minuscule voice within the Catholic Church, with only 168 listed members stretched across forty homes worldwide.

I suspect it remained small because it could not and would not accumulate the wealth and land other orders accrued through cattle colonialism and ecological imperialism during the Age of European Discovery and Conquest.

But small or not, the Ordo Minimorum, the Minims, is an Order of Pontifical Right, approved by the Holy See, authentically Christian and has been for six centuries. And that tradition should matter to other ethical vegans in Christendom, particularly if they’re believers.

Vegans and animal liberationists today may be in the minority, but thanks to Saint Francis of Paola and the Minims, it is a minority with a long tradition, neither exotic nor alien. ⸎

Epilogue

I hope this article helps educate vegans, anti-speciesists and animal liberationists, particularly in Christian countries, about the Order of Minims, its Paolan vow and St. Francis of Paola’s “animal liberation theology.” Together, they show that even within the Church, there is precedent, tradition, and the presence of allies on these issues.

Footnotes

While only wool is excepted, due consideration must be given to the story of Martinello, Francis’ companion sheep, said to have been killed for food and then miraculously revived by Francis. A post-mortem open rescue. ↩︎

Old Italian Text:

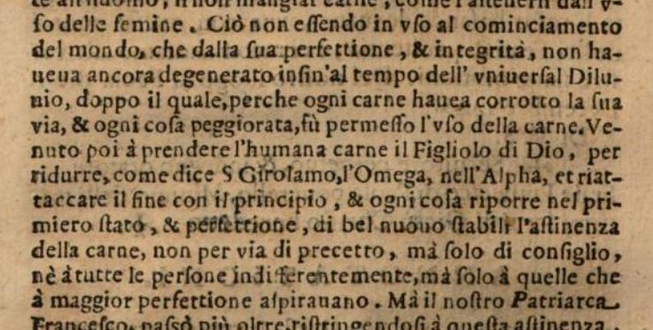

Ciò [mangiare carne] non essendo in uso al cominciamento del mondo, che dalla sua perfezione e integrità non avea ancora degenerato, infino al tempo del universale diluvio; dopo il quale, perché ogni carne avea corrotto la sua via, e ogni cosa peggiorata, fu permesso l’uso della carne. Venuto poi a prendere l’umana carne il Figliolo di Dio, per ridurre, come dice San Girolamo, l’Omega nell’Alpha, e riattaccare il fine con il principio, e ogni cosa riporre nel primiero stato e perfezione di bel nuovo, stabilì l’astinenza della carne non per via di precetto, ma solo di consiglio; né a tutte le persone indifferentemente, ma solo a quelle che a maggior perfezione aspiravano.

English Translation:

This [meat eating] was not in use at the beginning of the world, which had not yet degenerated from its original perfection and integrity, until the time of the universal flood; after which, because all flesh had corrupted its way and everything had worsened, the use of meat was permitted. Then, the Son of God having taken on human flesh, in order (as Saint Jerome says) to bring the Omega back to the Alpha, to reattach the end to the beginning, and to restore all things to their original state and perfection anew, established abstinence from meat not by way of commandment, but only as counsel; and not for all persons indiscriminately, but only for those who aspired to greater perfection.

Source: Francesco di Longobardi, Centuria di lettere del glorioso patriarca S. Francesco di Paola (Florence?: Ignatio de Lazzeri, 1655), annotation II to Letter XI, p. 73. ↩︎

Concentrated animal feeding operations (CAFOs) are intense feeding operations used to quickly increase the weight of animals before slaughter, which cause great suffering and environmental damage. Ventilation shutdowns are used to suffocate large numbers of animals over the course of a few hours to cull them. ↩︎

— Your Correspondent accepts and appreciates Stripe Donations. —